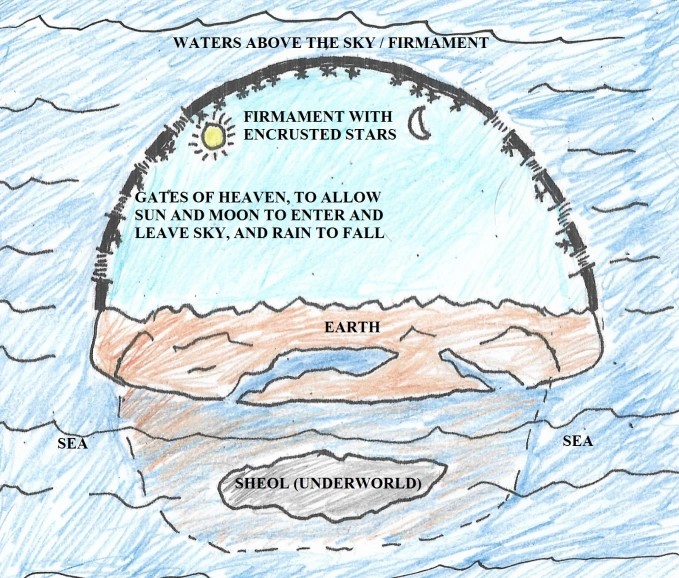

The first key to understanding ancient religion is realizing that the ancients had a vastly different view of the universe to ourselves. The earliest civilizations believed in a flat earth which was either a circle or a square, depending on the tradition. Above the earth, the heavens / sky was seen as being a dome. The sky was the realm of gods, stars, the sun and moon, but also clouds, thunder, lightning and rain.

This simplistic cosmic model of sky above and earth below was central to ancient religion and cosmology, including both the Bible and Quran. The ancient Sumerians were one of the earliest civilizations, their word for the universe was an-ki, quite literally heaven-earth. We find the same thing in China, where the word tian means ‘heaven’, ‘sky’ and ‘god’. The ancient Chinese word for universe was tian di, again literally ‘heaven-earth’.

Certain cultures believed there was a gloomy underworld beneath the earth, inhabited by the dead. The Sumerians called this place Kur, the Hebrews / Bible writers Sheol, and the Greeks Hades. A Sumerian text called Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Underworld describes this tripartite division of the cosmos at creation, placing each part under the rule of a particular deity, ‘When An had taken the heavens for himself, when Enlil had taken the earth for himself, when the Underworld had been given to Ereshkigal as a gift’ (Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Underworld 12-15). The Epic of Gilgamesh describes this gloomy underworld with,

‘The house where residents are deprived of light,

where soil is their sustenance and clay their food,

where they are clad like birds in coats of feathers,

and see no light, but dwell in darkness.’ (The Epic of Gilgamesh 7.187-190)

Homer described Hades as ‘the House of Death, far in the hidden depths below the earth’ (The Odyssey 24.224-5). In the Bible, the Book of Job describes the Jewish underworld Sheol as ‘the place of no return, the land of gloom and utter darkness. A land of gloom, as darkness itself, and of the shadow of death, without any order, where the light is as utter darkness’ (Job 10.21-22). In the New Testament. Paul’s letter to the Philippians also mentions this simple tripartite cosmos, ‘At the name of Jesus, every knee should bend, of those in heaven, and on the earth, and under the earth’ (Philippians 2.10).

The sky dome was sometimes believed to be supported by pillars above a flat earth. We read of these pillars in the Bible. The book of Job states of Yahweh, ‘The pillars of the heavens tremble and are amazed at his rebuke’ (Job 26.11). In 1 Samuel we read, ‘The pillars of the earth belong to Yahweh, on them he has placed the world’ (1 Samuel 2.8).

The ancient Egyptians also appear to have believed in pillars supporting the sky dome, The Pyramid Texts state, ‘I take possession of the sky, its pillars and its stars’ (Utterance 510). The same thing is true of the early Greeks. Homer wrote, ‘Atlas, wicked titan who sounds the deep in all its depths, whose shoulders lift on high the colossal pillars thrusting earth and sky apart’ (The Odyssey 1.62-65). The Orphic Hymns speak of ‘the four-pillared cosmos’ (OH 1.38).

The landmass of the earth was often believed to sit on a vast sea of water, which also surrounded the sky, presumably explaining how water fell from the sky. This also explained how water could be found underground and come up through springs and artesian wells. This is described in Genesis,

‘God said, “Let there be a vault in the middle of the waters to separate water from water.” So God made the vault and separated the water under the vault from the water above it. And it was so. God called the vault “sky.”’ (Genesis 1.6-8)

Elsewhere we are told in the Psalms, ‘Praise him highest heavens, and the waters that are above the sky’ (Psalm 148.4).

The sky was believed to have doors, gates and windows in it that gods could open to let rain fall, or let mythical floods happen. These openings also allowed the sun and moon to enter the sky. We read of this in Isaiah, ‘The windows of the sky are opened, the foundations of the earth shake’ (Isaiah 24.18).

The Pyramid Texts continually mention these doors, such as in Utterance 510, ‘The doors of the sky are opened, the doors of the firmament are thrown open for me at dawn.’ In numerous Akkadian and Sumerian texts, the sun, moon, Venus, and the stars are said to enter and leave the heavens through gates. A Jewish text called 1 Enoch displays the simplistic view of the cosmos that the Jews held when it was written in the third century BCE,

‘The sun rises in the gates of heaven that are in the east and it sets in the gates of heaven that are in the west. I saw six gates from which the sun rises and six gates in which the sun sets and the moon rises and sets in these gates, and the leaders of the stars and those whom they lead.’ (1 Enoch 72.2-3)

Numerous ancient civilizations believed the sky dome was made of metal, perhaps because metallic meteorites that had fallen from the sky were well known in ancient times. They were often considered sacred stones from the gods. The black stone in the Kaaba in Mecca may be one such stone that still exists as a central focus for a world religion. The book of Job states of Yahweh, ‘Can you spread [beat] out the vault of the skies, as he does, hard as a mirror of cast metal’ (Job 37.18).

The Hebrew word for this sky dome is translated in English as ‘firmament’, which betrays its firm, solid nature. The original Hebrew word is raqiya, which derives from the Hebrew root riqqua, meaning ‘beaten out’, like a metallic bowl or plate. he book of Ezekiel describes the heavenly firmament as, ‘spread out…what appeared to be a dome, sparkling like ice, and awesome’ (Ezekiel 1.22).

The ancient Greeks probably also originally believed in a metallic sky dome. Homer wrote of ‘the iron heaven’ and ‘the bronze heaven’ (The Odyssey 15.329, The Iliad 5.504 and 17.425). The sixth century BCE poems of Theognis state, ‘May the great broad sky of bronze fall on my head’ (Eulegies 869). We find the same belief in ancient Egypt too, the ancient Egyptian word for the firmament was closely related to their word for iron. Meteoric iron was a sacred metal in ancient Egypt. The tools involved in the Opening of the Mouth ceremony that was believed to release a dead pharaoh’s soul to travel tothe stars were probably made of meteoric iron.

The Pyramid Texts state of the heavenly ascent of the dead pharaoh, ‘the doors of…the firmament are opened for me, the doors of iron that are in the starry sky are thrown open for me’ (Utterance 469). Over 1000 years later, Tutankhamun was buried with a dagger made of meteoric iron, as well as meteoric iron blades and chisels that may have been used in his Opening of the Mouth ceremony. The Zoroastrians believed the same thing, the Bundahishn talks of ‘the shining and visible sky, which is very distant, and of steel, of shining steel’ (Greater Bundahishn 1.6).

The earth was also believed to be stationary, the heavenly dome (or later globe) was believed to rotate above and around it. We find mentions of this belief that the landmass of the earth was fixed and motionless in the Bible. Psalms states that ‘the earth is fixed, immovable and firm’ (Psalms 93.1 & 96.10). Psalms also states of Yahweh,

‘You have spread out the heavens like a tent…

…You fixed the earth on its foundation,

It can never be moved.’ (Psalms 104.2-5)

We find a similar description of the cosmos and God’s place in it in a pagan hymn from the Corpus Hermeticum.

‘Be opened, you heavens, and you winds be still.

Let the immortal sphere of heaven receive my utterance.

For I am about to sing the praise of him who created all things,

who fixed the earth, and hung heaven above.’ (Libellus XIII)

By the fourth century BCE, the Greeks had come to the realisation that the world was in fact spherical, and the universe was seen as a large orb fixed with stars that revolved around the stationary central earth. This view of the universe is called the geocentric model (the earth being at the centre of the cosmos). The geocentric model was in use for almost 2000 years, below is a depiction of it from the Renaissance.

In both these ancient models of the cosmos, seven planets were believed to revolve around / above the central earth. The planets in the ancient system were the moon, the sun, and the five planets visible with the naked eye (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn). They were ordered away from the earth according to their orbital period.

The moon was believed to hold the nearest orbit to earth (27 days), then Mercury (88 days), Venus (225 days), the sun (365 days – i.e. that of the earth around the sun in reality), Mars (687 days), Jupiter (4333 days) and finally Saturn (10,759 days). The ancients thought each planet took this long to circle the earth, rather than the sun, and each of these seven planets were believed to rotate round the earth in independent orbits.

The word ‘planet’ derives from the Greek planetes, which means ‘wanderer’. The Greeks saw the planets as wanderers because they appear from earth to move through the heavens independently, as opposed to the stars of the constellations, that all move together. The Greeks believed that the stars of the constellations were all fixed to an outer orb that encapsulated the universe.

All in all, there were reckoned to be nine concentric cosmic globes; the central earth, the seven planets each in their own orbit, and the outer globe that contained the constellations. Cicero (106 – 43 BCE) is a good source for understanding the geocentric model. He wrote,

‘The universe is held together by nine concentric spheres. The outermost sphere is heaven itself, and it includes and embraces the rest. For it is the Supreme God in person, enclosing and comprehending everything that exists, that is to say all the stars which are fixed in the sky yet rotate upon their eternal courses. Within this outermost sphere are eight others. Seven of them contain the planets – a single one in each sphere…the earth, the ninth and lowest of the spheres, lies at the centre of the universe. The earth remains fixed and without motion.’ (The Dream of Scipio 9)

model

The Corpus Hermeticum also mentions the seven planetary spheres when it describes the creation of the cosmos,

‘And heaven appeared, with its seven spheres, and the gods, visible in starry forms, with all their constellations. And heaven revolved, and began to run its circling course.’ ( Libellus III)

This model of the universe still held sway in medieval Europe. In Christopher Marlowe’s play Doctor Faustus, the cosmic spheres are described by Mephistopheles,

‘As are the elements, such are the spheres,

Mutually folded in each other’s orb;

And, Faustus, all jointly move upon one axletree,

Whose terminine is termed the world’s wide pole.’ (Doctor Faustus 667 – 70)

Leave a comment