Mithraism was a Roman mystery religion, dating to the first few centuries CE. The central image of Mithraism was the so-called ‘tauroctony’ (bull-slaying) scene in which the god Mithras stabs a bull in the shoulder. The tauroctony scene was often depicted at the centre of a zodiacal wheel, and it’s long been thought that the scene is a mythological representation of astronomical / cosmological beliefs.

Many authors have suggested that the bull may represent the constellation Taurus, several have gone further and suggested that Mithras himself may represent a constellation such as Perseus or Orion. There are problems with this interpretation though, as the bull in tauroctony scenes always faces to the right, whereas the constellation of Taurus faces to the left in the night sky. If the bull was supposed to represent Taurus, surely it would be facing left and not right. There’s also the problem that Taurus also always appears in any zodiac surrounding the tauroctony, where it always faces to the left and not the right, again suggesting the central bull may not represent Taurus.

It may be relevant that Mithras is usually depicted stabbing the bull in the shoulder, this occurs in an estimated 80% of the known scenes. The Bull’s Shoulder / Calf was the Egyptian name for the asterism of the Big Dipper. It was sometimes represented in Egyptian art as a bull, like on the ceiling of the tomb of Seti I. The round zodiac from Dendera has the bull’s thigh located at the centre of the heavens.

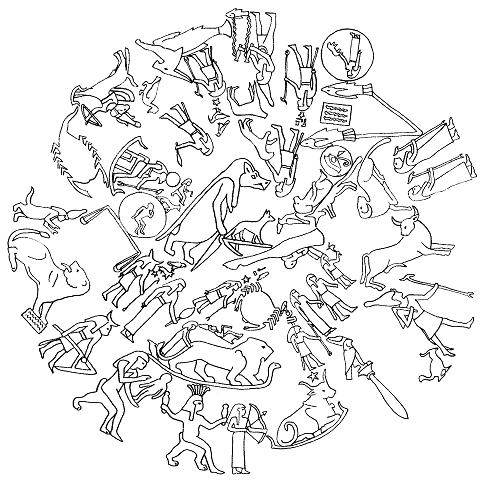

The Round Zodiac from Dendera dating from the first century BCE. At the centre we find a canid and the bull’s thigh.

The seven stars of the Big Dipper kept this bovine connection throughout antiquity, and well into Roman times. Hyginus wrote of Ursa Major, ‘Two of the seven stars which seemed of equal size and closest together were considered oxen’ (Astronomica 2.2.2). They may also have kept this bovine link in the Latin name for them, the Septemtriones (Septem being the Latin for seven, Triones being the plural of the Latin for plough ox). This may also explain the name of the neighbouring constellation Bootes – the ‘ox-driver’ or ‘ploughman’.

The so-called Mithras Liturgy suggests that Mithraists may also have called Ursa Major the bull’s shoulder. This manuscript describes a ritual ascent made by an initiate to see Mithras, in which he has to use magical words, glyphs and seals to pass various celestial sentinels en route to heaven. Mithras is described as being located at the celestial pole, holding the bull’s shoulder (the seven stars of the Big Dipper). On his ascent to the pole, the initiate first has to pass the ‘seven immortal gods of the cosmos’ (line 620) and Helios (the Sun).

‘Now when they [the seven Pole Lords] take their place, here and there, in order, look in the air and you will see lightning bolts going down, and lights flashing, and the earth shaking, and a god descending, a god immensely great, having a bright appearance, youthful, golden-haired, with a white tunic and a golden crown and trousers, and holding in his right hand a golden shoulder of a young bull: this is the Bear which moves and turns heaven around, moving upward and downward in accordance with the hour. Then you will see lightning bolts leaping from his eyes and stars from his body.’ (The Mithras Liturgy 690 – 705)

In the zodiac on the ceiling of the Mithraeum at Ponza, the constellation of Ursa Major was given special significance by being placed at the centre. Ursa Minor and Draco are depicted alongside it, and are the only constellations depicted apart from the zodiac. We may find this constellation elsewhere in Mithraism. Several Mithraic reliefs depict a purification rite in which an initiate is struck by the father of the congregation with the leg and shoulder blade of a bull. This act mirrors mythological scenes in which Mithras strikes Helios (the sun) with the same bull’s haunch. We also have depictions of Mithras turning the zodiacal wheel, which could again link him to the pole / axis.

The blood that issues forth from the bull’s shoulder is often depicted being licked by a dog and a snake. These might represent Ursa Minor (possibly depicted as a canid on the Dendera zodiac) and Draco if the pierced bull’s shoulder represented Ursa Major. Ursa Minor was also called Cynosura – ‘the dog’s tail’ by the Greeks. The Dendera round zodiac depicts a canid at its centre, suggesting the ancient Egyptians represented a star or constellation near the pole with a canid. This canid constellation may have represented the god Wepwawet, who was involved in the opening of the mouth ceremony. This ritual allowed released the soul of the deceased king from the mummified body to ascend to the heavens. Utterance 302 of The Pyramid Texts state that, ‘Wepwawet has caused me to fly up to the sky among my brethren the gods.’

Statues and depictions of humanoid figures (often with a lion’s head) entwined with a snake have been found at numerous Mithraic sites. They may also depict a god or celestial power at the world axis. They are sometimes depicted stood rigidly on top of the cosmic globe and occasionally at the centre of a zodiac, again suggesting they may represent a power at the axis. The snake entwined figures are similar to depictions of a tree wrapped with a serpent from Greek art, and depictions of the Garden of Eden and the Garden of the Hesperides. These snakes probably depicted Draco, the serpentine constellation that entwines around the celestial pole.

These figures are winged and often have a lion’s head, which might also link them to Draco. There are ancient Sumerian cylinder seals depicting the god Enlil riding in his wagon (the Big Dipper). The wagon is pulled by a winged lion that may represent the stars of Draco.

Leave a comment